Urban Agriculture Impacts Social Health and Economic a Literature Review

Food Organization Revolution: The Potential of Urban Agriculture

Next time y'all're eating a banana, expect at the label on information technology. Where is it from? Most likely, it was grown on a S American subcontract located over a one thousand miles abroad. This is true for most U.S. produce which on boilerplate travels near 1,500 miles to become from subcontract to plate (Weber & Matthews 2008). On that journey, approximately 400 kilograms of CO2, 50 grams of methane, and 20 grams of N2O were emitted into the atmosphere.

"Food miles" is the term for the altitude food travels from where it is grown or raised to where it is consumed. With U.S. food imports increasing and its transportation accounting for eleven% of yearly greenhouse gas emissions, the need for a shift towards locally sourced food spawned the locavore movement. A "locavore" is a person who only eats food grown inside 100 miles of them. Nevertheless, with over 80% of the world living in urban areas, many people don't have access to local farms and ranches.

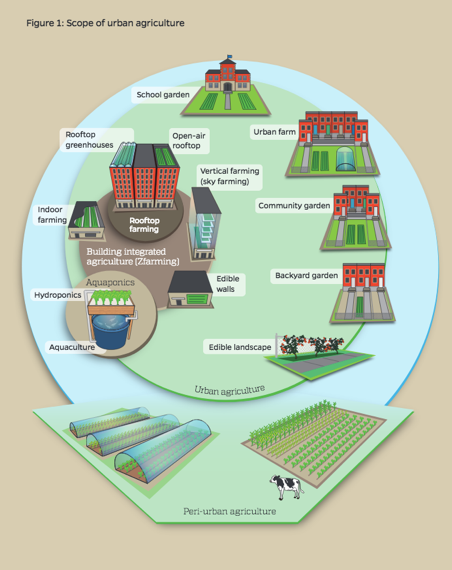

This disconnect between nutrient systems and the urban population has led to a lack of awareness in the natural resources essential to life which are now in a country of depletion. In order to combat this, farming needs to exist reintegrated into dense metropolitan environments. Urban agriculture has the potential to improve public health, community appointment, and environmental quality. It includes whatsoever privately, publically, or commercially owned farms, community gardens, building integrated farms, and indoor farms in an urban area (Effigy 1).

Public Wellness and Customs Date

These small, scattered urban farms use innovative growing methods to maximize food production in their express space. In 2010, 12.3 percent (15.6 meg) of U.S. households were food insecure at some time and ix.7 per centum of households lived more than one mile abroad from a supermarket (USDA, 2010). The improver of urban farms boosts the supply of fresh produce year round while improving low-income family'due south access to nutritious food. A study on the potential ecosystem services of urban agronomics found that cities accept the potential annual nutrient production of 100–180 million tons globally, making a pregnant impact on world hunger (Clinton et al. 2018).

In addition to nutrient security, urban agriculture strengthens the community by creating a sanctuary for social interaction where residents develop a sense of pride in their country. Throughout the enquiry done on the impacts of urban agriculture, the virtually observed touch was on customs development (Golden, 2013). The most direct impacts are seen in community gardens, where the natural setting helps interruption downwards social boundaries and unite the neighborhoods under a common goal to meliorate their environment.

Added benefits have been seen in youth gardening programs where children have been reported to brandish greater leadership skills, brand healthier choices, and prove increased interest in environmental activism (Santo et al. 2016). For instance, in Austin, Texas the organization Urban Roots uses food and farming to empower kids in their youth development program. Later farming at that place, thirteen-yr-onetime Alexis said, "I have basketball military camp [during the summertime], and I recall I desire to have vegetables instead of snacks later practice."

Environmental Quality

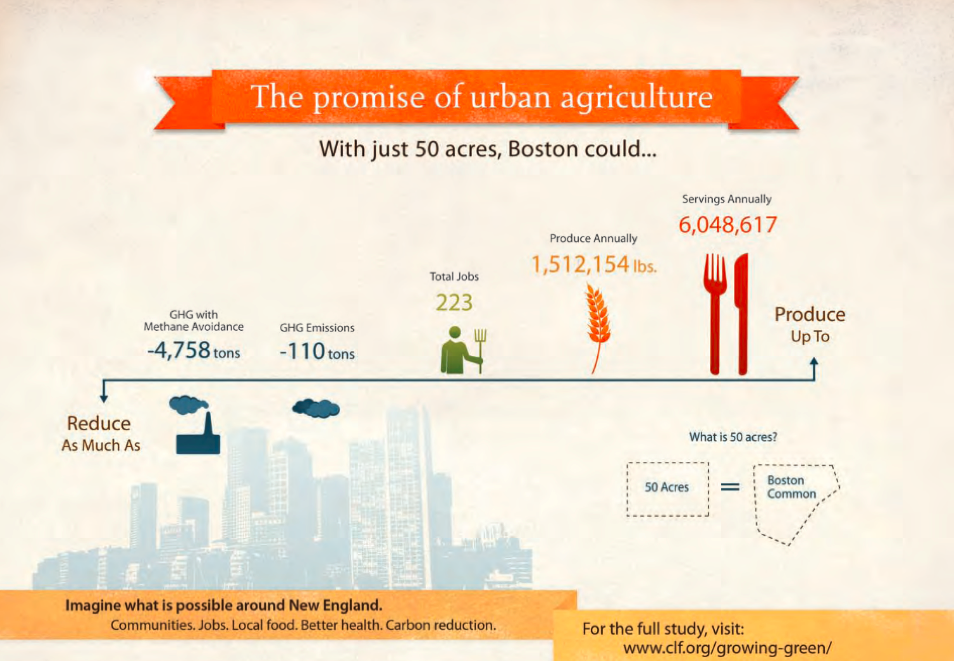

By just increasing greenspace in cities, urban agriculture improves air quality, biodiversity, soil quality, reduces runoff and combats the urban heat island issue. The plants growing in these gardens provide a habitat for bugs, birds, and other animals while filtering pollutants out of the air, reducing heat through transpiration procedure, increasing groundwater infiltration and decreasing soil erosion and compaction. The full utilization of available urban land for agriculture would save energy past fourteen to 15 billion kilowatt hours, increment nitrogen sequestration to between 100,000 and 170,000 tons, and decrease tempest water runoff between 45 and 57 billion cubic meters annually worldwide (Clinton et al. 2018). For case, in Boston, Massachusetts the dedication of just fifty acres to urban agriculture would sequester about 114 tons of carbon dioxide in soil per year and avoid iv,758 tons of greenhouse gas emissions while feeding an boosted 6 1000000 people (Brown et al. 2016)(Figure two).

The Reality of Urban farming: Austin, Texas

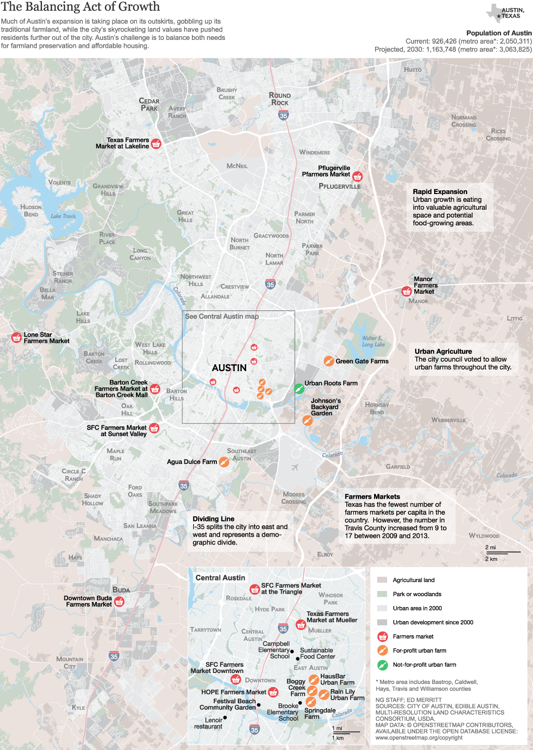

Austin, Texas is considered 1 of the leading cities in urban farming practices. The urban agriculture motility is highly encouraged by residents and well-supported with governmental policy. The Sustainable Urban Agriculture and Customs Garden Programme (SUACG) was created by Austin City Quango in 2009 to streamline the establishment of sustainable urban agriculture on metropolis land. The ordinance supports not only the enhancement of local food availability but also storm water collection likewise equally waste and energy reduction practices by directing the city manager to, "Initiate necessary lawmaking amendments to define urban farms as those which volition include using water conservation practices, composting, and non-polluting growing practices."(COA, 2009). Currently 23 urban farms and 52 community gardens thrive in Austin including Hausbar, Boggy creek, Springdale, Urban roots, Agua Dulce, Dark-green Gates and PEAS school community garden (Figure 3).

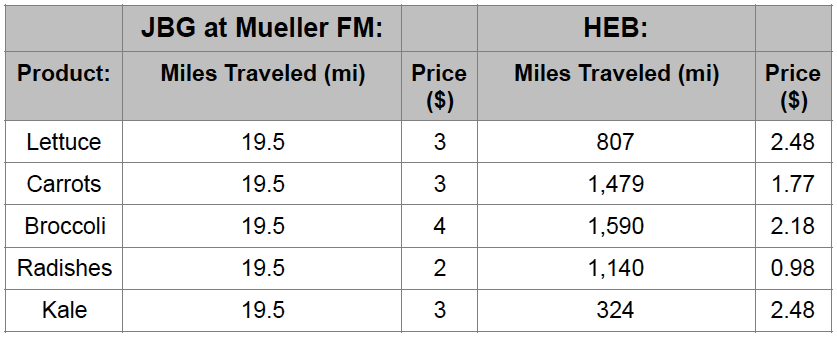

Despite institutional efforts, less than 1% of nutrient consumed by Austin residents is locally produced (USDA, 2012). This is largely due to the cost difference betwixt supermarket's and farmer's market's food. To better sympathise the price and feasibility of being a "locavore" I visited the Mueller Farmer'south market and compared the price and nutrient miles of local produce to HEB'due south produce (Figure 4). At the farmer's market, I gathered vegetable prices from Johnson'south Lawn Garden, a 20-acre family farm located east of downtown Austin. For some products, such as broccoli or radishes, the price was shut to double that of HEB. But for others, such as kale and lettuce, the price departure was closer to l cents.

The higher price of sustainably grown produce has led to a socio-economic stigma associated with shopping at local farms. With internet blog posts titled, "Apropos the unbearable whiteness of urban farming" and "Is urban farming simply for rich hipsters?" information technology seems similar urban farming is viewed as a trendy phase rather than a serious opportunity.

To understand how urban farmers are responding to this miracle I visited Dorsey Barger & Susan Hausmann, Owners of HausBar Urban Farm in East Austin. With their master buyers being upscale restaurants similar Uchi, Strange & Domestic and Wink, it is clear that their food is non attainable to depression-income Austinites. In response to critiques of their economical bias Barger says, "In that location's a huge educational thing going on here. Our [low-income] neighbors are benefiting very directly by seeing vegetables being grown, how chickens are raised, where eggs come up from…those things are very important."

Fighting the urban farming stigma, Austin'south sustainable food eye implemented the Double dollars' program, which doubles the dollar amount of Lone Star (SNAP), WIC and FMNP Vouchers so less affluent families tin can get more fruits and vegetables at SFC Farmers' Markets. Similarly, the SFC'due south Spread the Harvest project seeks to reduce fiscal barriers to food gardening by providing Central Texas schools, low-income residents and not-for-profit gardens, and other groups with complimentary gardening materials.

While Austin may be considered one of the leading cities for urban agronomics, the scale is still likewise small to see significant environmental and public health improvements. Between the high prices at these pocket-size-scale sustainable farms and the publics lack of environmental education, it seems a major shift towards locally sourced produce won't occur until food insecurity and resource depletion give u.s.a. no choice.

But as more than people appoint in community gardens, visit farmer's markets or simply walk past a local farm, they are connecting to the natural growing process. When citizens can watch their food grow and see the time and natural resource it requires, a new appreciation for the value of food is instilled and lodge as a whole becomes one footstep closer to a food system revolution.

Citations

Brownish, S., McIvor, K., & Snyder, E. H. (Eds.). (2016). Sowing seeds in the city: Ecosystem and municipal services. Springer.

Clinton, N., Stuhlmacher, M., Miles, A., Aragon, N. U., Wagner, M., Georgescu, Grand., . . . Gong, P. (2018). A Global Geospatial Ecosystem Services Guess of Urban Agriculture. Earth's Future, half dozen(1), 40–60. doi:x.1002/2017EF000536

Gilded, S. (2013). Urban agriculture impacts: Social, wellness, and economic: A literature review. University of California: California.

Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2012. (2014). The Air Pollution Consultant, 24(3), 1_17.

Nierenberg, D., Halweil, B., Starke, L., & Worldwatch, I. (2011). Country of the globe 2011: innovations that nourish the planet : a Worldwatch Establish report on progress toward a sustainable lodge (1st ed.). New York: W.Due west. Norton & Co.

Santo, R., Palmer, A., & Kim, B. (2016). Vacant lots to vibrant plots: A review of the benefits and limitations of urban agriculture.

Sustainable Urban Agriculture and Customs Garden Ordinance, Res. 20091119 § 065 (2009).

USDA-NASS (2012). Demography of Agriculture U.s. Summary and Land Data. Retrieved from https://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/2012.

Ver Ploeg, G., Economic Enquiry, South., Department of, A., & United, South. (2012). Access to affordable and nutritious food: updated estimates of distance to supermarkets using 2010 data. Retrieved from Washington, D.C.

Weber, C. 50., & Matthews, H. S. (2008). Food-Miles and the Relative Climate Impacts of Food Choices in the United states of america. Environmental Science & Technology, 42(10), 3508–3513. doi:10.1021/es702969f

Source: https://medium.com/the-healthy-city/food-system-revolution-the-potential-of-urban-agriculture-f9b03f2a7120

0 Response to "Urban Agriculture Impacts Social Health and Economic a Literature Review"

Post a Comment